I am guilty of focusing too much on disparities sometimes, of talking about the deficits inflicted on communities rather than the assets they have built and sustained. When gaps in food, health, and nutrition are so huge, bringing attention to the problems can feel urgent. But that's not necessarily the best way to talk about those problems, and it is certainly not the only way.

It's not empowering to hear about all the injustices suffered by your community, all the ways structural oppression makes life harder for people who look like you. But hope and possibility can be empowering. They lift us out of the reality of what is and transport us into what could be or back into the past, what has been. When I did Equity & Results' Antiracist Results-Based Accountability training earlier this year (recommended!), we began our work by envisioning what racial equity would look like in our communities. What would we see, hear, smell, taste? Down in the mucky work of thinking through programs, indicators, and what to measure, we had that concrete vision of the future we were working toward, a guiding star.

Just as important is hearing stories of success, especially about BIPOC communities who created their own change, but these types of stories feel rare in mainstream media. In the US, we love the individual innovator, the changemaker with big and bold ideas, the (often white) savior. We're less interested in the slow, messy, usually nonlinear work of communal, community-driven change. It's not sexy. There's probably a lot of conversations about permits and zoning. You can't cast Joseph Gordon-Levitt in the Hulu movie version of it; there is no lead.

I'm writing this not knowing the results yet of Tuesday's election, what the next couple years will hold for us politically. At moments like these, when the near future feels fraught, I find it grounding to hear stories from the past, and to remember that history is long, and that beauty has flourished even in the face of fear and ugliness.

Today I want to talk about Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC). Most of this information comes from Monica M. White's excellent book Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement. She also wrote a 2017 paper called “‘A pig and a garden’: Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Farms Cooperative.”

Down where we are, food is used as a political weapon. But if you have a pig in your backyard, if you have some vegetables in your garden, you can feed yourself and your family, and nobody can push you around. If we have something like some pigs and some gardens and a few things like that, even if we have no jobs, we can eat and we can look after our families.

– Fannie Lou Hamer

The story of Freedom Farm Cooperative actually does have a star; it was civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer. Her parents were sharecroppers, and she began working in the cotton fields at age six. In 1962, she was fired and evicted from the Mississippi plantation where she had worked for 18 years because she refused to withdraw her application for voter registration. Later she said, "They kicked me off the plantation, they set me free. It's the best thing that could happen. Now I can work for my people."

In Jim Crow Mississippi, she saw how white lawmakers and local officials were using economic and political disenfranchisement and the threat of starvation to oppress a Black population who often relied on agricultural work on white-owned farms to survive. She said, "If you are a Negro and vote, if you persist in dreams of black power to win some measure of freedom in white controlled counties, you go hungry."

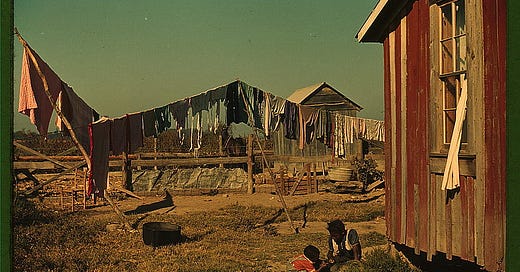

Instead of leaving the South in search of economic opportunity, as more than three million Black people did between 1940 and 1960, she founded Freedom Farm Cooperative, starting with 40 acres of land in Sunflower County, Mississippi. She knew the community's success relied on more than just alleviating hunger, so in addition to establishing an agricultural cooperative, FFC also sought to build affordable and safe housing for its families, and create a small business incubator that would provide job training and resources for members. The goal was to collectively share resources and create economic self-sufficiency, in order to build political power and further resist oppression.

The "Bank of Pigs" was one way FFC pooled resources in order to better provide for the collective. When the farm received a donation of 50 pigs in 1969, instead of slaughtering them for food immediately, they cared for them communally and bred them, building up a "bank" that went from providing over 100 families with female pigs in 1969 to more than 865 families in 1973. After a family’s pig had a litter of piglets, they had to give two piglets back to the collective, and could raise the remaining pigs for meat or for sale, which provided supplemental income.

The crops grown on the farm also supported self-sufficiency alongside collective well-being. Greens, kale, turnips, corn, sweet potatoes, okra, and a couple types of beans provided food for cooperative members, while a portion of the food grown in community gardens was given to families in need, as far away as Chicago. Cash crops like soybeans, wheat, and cucumbers (for contracts with pickle companies) were grown and sold to pay the mortgage on the land.

Having that pig and that garden were crucial. Growing your own food—rather than relying on a plantation commissary or some other white-controlled entity—ensured that, no matter what harm or harassment might come your way, you would not starve.

But agriculture was only part of the work. Freedom Farm Cooperative was the site of one of the first Head Start programs in the region. In a county where more than 90 percent of Black people lived in structures classified as "dilapidated and deteriorating," and 75 percent of houses had no running water, FFC purchased land and secured funding to build 80 homes with electricity, running water, and indoor plumbing for cooperative members. FFC had sewing cooperatives that made new clothing and upcycled used clothing. One of them had on-site childcare for its employees.

The cooperative ended in the mid-1970s, after outside funding declined, and the region endured droughts followed by flooding, which decimated that year's harvest. Without the sale of cash crops to pay its mortgage, the organization had to shut down. A few years later, it had to sell its remaining land to pay overdue taxes.

But the end of the Freedom Farm Cooperative does not mean the end of its influence or inspiration. In the US, we often see failure as some kind of "proof" that an idea was not a good one, but I don't agree with that at all. As Monica M. White puts it:

FFC created an oasis of self-reliance and self-determination in a landscape of oppression maintained in part by deprivation.

An oasis. Fighting deprivation by creating a place of plenty, where they had enough because they shared it together, and when there was more than they needed, they shared more—even with the friends and family who hadn't been able to stay in the South, the ones who probably missed the taste of homegrown tomatoes and okra, missed being with a community of people they'd known all their lives, missed the feeling of hands in the earth. Even a year of that kind of plenty seems like a gift. Four years of it? A minor miracle.

Such a place existed. And that means something.

More about Freedom Farm Collective

The Civil Rights Icon Who Saw Freedom in Farming - Atlas Obscura

Fannie Lou Hamer's Pioneering Food Activism Is a Model for Today - Food & Wine

thank you for sharing this story! we need these “messier” community level changes from history to be more mainstream. I would highly recommend Offshoot’s piece on Belo Horizonte for another story of hope in the food system :)