"Dismantling Diet Culture Will Not Make It Safer for Us to Exist"

On rewriting the stories of Black women's bodies, with dietitian Jessica Wilson

Although I am not a dietitian who specializes in eating disorders, I have found community in that space, in part because those whose work involves pushing back against fatphobia and food shaming are—like me—deeply disappointed in the nutrition status quo. It's also because, in 2020, there was widespread discussion of how the West's fear and hatred of fatness began as a reaction to Black women's bodies. Read Fearing the Black Body! and BMI is racist! became rallying cries and a signal that you understood fat oppression was, for Black women, far more oppressive than it was for white women. It was summer of 2020, you know how it was. Many lists of Black writers and thinkers and influencers were shared. White people made pledges to Do Better, to Listen More, to Uplift Others.

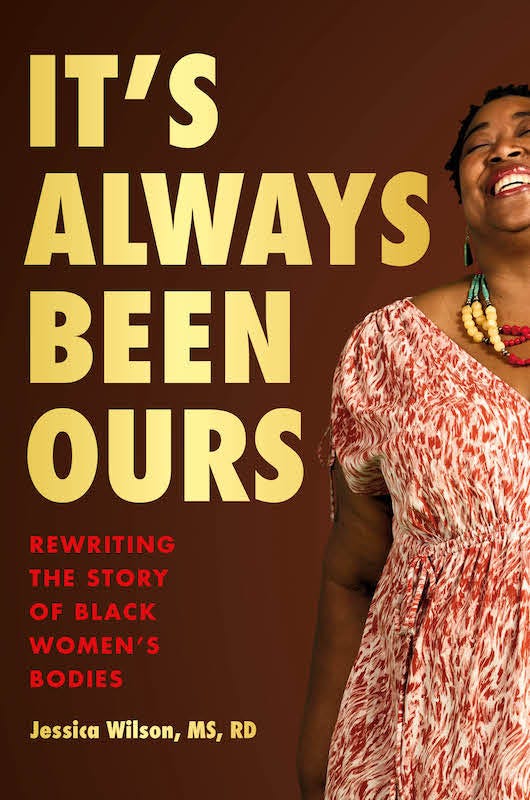

More than two years later, it feels like the wider world has started talking more about weight stigma and the dangers of diet culture—but more often than not, Black people are not part of the conversation, much less at its center. So it was refreshing to pick up Jessica Wilson's forthcoming book, It's Always Been Ours: Rewriting the Story of Black Women's Bodies, a work that centers Black women's stories and relationships with their bodies. Jessica is a clinical dietitian, consultant and author, whose experiences navigating the dietetic fields as a Black, queer dietitian have been featured on public radio shows and in print media, including the New York Times, Bustle, and Cronkite News.

The book's essays cover a wide range of topics—her work in eating disorder treatment, Lizzo and the expectation of "respectibility" in Black culture, the problems with body positivity/toxitivity, her Get Out-like experience at a public health nutrition conference, and more—expressed with a clarity and deadpan honesty that makes you understand why her clients appreciate her. There is no sugar coating the truth. Listen, or don't. She's still going to speak it.

I had a great time talking to her about why eating cake in public is not liberation, the paternalism of public health nutrition, and what a truly joyful Instagram scroll would look like. I hope you'll enjoy it too.

“Society is oftentimes not a safe place for us to exist.”

You start off the book with a bang, in your chapter "It Isn't Diet Culture, It's White Supremacy," and I think you explain so clearly how racism is not just one tentacle on a "hydra-headed beast,1" or just the roots of diet culture; it is the beast and the tree. You point out that for Black women, the end of fat oppression will not mean liberation. It's not about watching Reels of thin, white women eating cake.

So while it feels like there has been a shift in talking about fatphobia and dismantling diet culture, at the same time it's very much the same old story, centering white women's bodies and experiences. What are the stories that aren't being told about Black women's relationships to their bodies, and their experiences?

The body stories of Black women who are conforming and transforming their bodies in ways to be safer in society and to survive in society are the stories that are always under the context of this thin ideal. The pursuit of thinness is often the pursuit of safety and survival in a world that is always telling us we're too much. So when we chalk it up again to thinness as a beauty norm or something that we're trying to achieve because of the male gaze, we're really disregarding the experiences of Black women and the realities that society is oftentimes not a safe place for us to exist.

I think another one that has come up more recently is the story of body modifications and BBLs [Brazilian butt lifts] for Black women, and how much the Black community shames and says things like, You should just love your body and Why would you ever do that to your body? It's beautiful. And those things can be true. But that shaming doesn't leave space for conversations about the levers of white supremacy that are always working in the background, that make us try to make ourselves more desirable, palatable, and safer.

“That's nice. That's not the work.”

In our initial conversation, I mentioned how I was feeling like the anti-diet movement seemed to be veering into some of the problems of second-wave feminism, so I was happy to see you had already written about that connection in your book. You wrote, "When white women's experiences are centered in stories about food and bodies, we see second-wave feminism's continued influence. Everyone's body liberation becomes tied to those with much of the privilege and societal capital." And then you quote a white fat activist who describes a vision of "liberation" that is completely focused on the individual and disconnected from systemic oppression.

Where do you see echoes of second wave feminism in the anti-diet space, and how can we stop history from repeating itself?

Honestly, it continues today, right? That's the same line about what diet culture is, and it's completely focused on the individual again. Sure, there's the: Society is telling us to do all of these things. Eat these ways, chase that ideal. So you can think yourself into eating cake in public, and that's fine, and you can think yourself into knowing that you're healthy, at whatever size you are. That's nice. That's not the work. That's the internal work. You can think those things and believe those things yourself, but then you still have to go outside.

What is the solution? I want to say something that's more profound than "intersectional feminism," because there's always something beyond feminism, of course. I'm thinking about neurodivergent folks and kids...

Are there any spaces where you are seeing that kind of intersectional work happen?

Yes, so I work right now at Lyon-Martin Health Services, and their intersection is very much trans care and the intersection of fat liberation, and then I come in with the intersection of food. So there really is a sense of possibility.

I see Naureen [Hunani] doing the intersections of neurodivergence and food. I am hoping that there can be a confluence of all of us who are focusing perhaps on one intersection, so that we can become like a giant Venn diagram rather than having just food and bodies trans care, or food and bodies and neurodivergence, because there is so much overlap. The Venn diagram is vast, and I feel like because we're so new to the intersections of food and bodies in a way that doesn't center thin white women, that we're figuring it out as we go along. So I would love for all of us at some point to come together, and share what we know.

I think in the end it is sitting in front of your client and really letting go of everything that you've been taught, which is wild. And that is so hard for clinicians, because we're taught to have an answer when somebody comes into our office. They ask a question and we answer it. That's how it's supposed to go. So those of us who have been seeing mostly Black women or trans folks or neurodivergent folks, how can we put this into practice, so that anyone who comes and sits in front of us, we're able to ask the right questions to actually understand what they need, rather than what we think they need. That's my dream.

“There was zero intention to change anything.”

"Health Is Killing Us"—the chapter about your panel on health disparities at the Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives conference—was particularly interesting for me, as my training is in public health, and the school I went to is well-known for its culinary medicine program. In theory, I thought it was great, but when I was actually in the teaching kitchen, it was such a judgmental, toxic, "One Right Way" kind of space that felt so disconnected from the world of New Orleans, which is so joyful around food and Black culture. Reading this chapter, and knowing the conference organizers provide the basis for culinary medicine programs, it made a lot more sense to me that my experience felt like that.

To be honest, the whole chapter read like a horror movie—in a very effective way. I was feeling so much tension and fear, like, "Jessica! Get out! It's the sunken place!" You were surrounded by wealthy white people who were tokenizing you, yet also dismissing the information you were there to provide, about health disparities and medical racism.

What did you take away from that experience? Has it changed how you view researchers, people in public health, or others that work in that space?

A greater understanding of the paternalism [in public health]. I had seen it myself and in my interactions, but I didn't know that it was standard issue for public health, especially leaders that talk about health disparities. It sounded like a good idea to have somebody ask me to talk about health disparities, but I realized how much of a check box it truly was, while there was zero intention to change anything. I was surprised by the performative aspect of public health in that moment.

And I realized how important both to identity and career legacy it is to uphold things like the Mediterranean diet and the idea that fatness is worth fearing.

Yes, it was very striking that you had to check in with your editor to make sure you wouldn't lose your book deal when you found out Walter Willett might disagree with your planned presentation on medical racism and fatphobia.

Katherine [Flegal]'s legacy is that she was bullied by Walter2, not all this other great stuff that she did.

“It's easier to point to one singular person.”

It was interesting to then see it contrasted with your trip to the Goop Convention, which honestly – although you were having bad reactions to the food – seemed like a more welcoming and less judgmental space. It made me think about how people spend so much energy making fun of wellness, making fun of Goop and Gwyneth, and even getting angry with her. When in reality Walter Willett and others working in institutions like the Harvard School of Public Health have much more power than she does, and they are held up as people who are doing great things in the world, rather than ridiculed. Experiencing both worlds in your book, why do you think there is that difference in how they're treated?

It's easy to point a finger at a singular person, and Gwyneth makes herself so prominent within Goop. So it's easy to say "this person and this brand." When we're looking at public health, it's really hard to say that every research institution invested in public health is the problem. I also think Gwyneth's lifestyle has so many aspects that are unrelatable that they become funny. And it's also easy to just chalk up everything that is wrong with the way that we're buying things that we don't need, to a singular person and a singular brand.

We're not looking at everything that public health makes us buy, like quinoa and kale, for example. How much are we spending on that? How much are we spending on groceries because we get food respectability from shopping at Whole Foods, and buying foods that we would never buy, except we've been shamed by society into doing so. We're able to look at [Moon Juice] dusts and collagen and all those things, and it's silly to think about those things, or to even laugh at people who are spending so much money on those things. But look at where we're shopping, and how much money people are spending on basically fancy groceries, when folks like me go to the cheapest store. It might not be the cleanest. It's not in neighborhoods that are desirable, but I don't spend that much money on groceries.

I think it's easier also to point to one singular person who is perhaps making us feel bad about our bodies, rather than a system in which we're supposed to function and get health care.

I love how you end your book with descriptions of Black joy, both yours and your friends', and you talk about what products and services you would offer if you had a lifestyle brand that centered joy instead of "health" or "wellness." Currently on social media—including in the anti-diet space—Black women, their bodies and their joy are not centered in the way you envision. If they were, what would you see when you scrolled through Instagram or TikTok? What's your dream scroll?

People resting. People napping, specifically. People laughing. Black women laughing loudly would be something that I would love to see in my feed. People outdoors together. And people enjoying being basic. So telling me what you got from Target today would be just a lot of fun for me. I'd love to see people and their dogs, people and their cats on my feed all the time. Food puns…love them. I don't see enough of them. And a real and honest interpretation of people sitting down to their food, and being like, "It's been eight hours, this has been my shift today. This is the reality of what my eating looks like."

What else do I want on my feed? …Black folks playing in the dirt. I think that's good. That's my list of like 20 things.

Thank you, Jessica! To support Jessica's work, you can preorder her book (release date is February 7), and follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

From the book: “Matt McGorry, an actor and body image influencer…shared that he read both Fearing the Black Body and Anti-Diet. His analysis was that diet culture and fatphobia make up ‘a hydra-headed beast, and that race is but one tentacle.’”

I didn’t know about this truly wild nutrition science feud until I read Jessica’s book. Katherine Flegal worked at the CDC and published an article in 2005 that found that the association between obesity and mortality was much less than previously publicized by the CDC, and that overweight classification had a slight but statistically significant association with fewer deaths than “normal” weight.

Walter Willett, a well-known professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and others at Harvard School of Public Health did not like these results, despite their scientific rigor and consistency with other published findings, and went out of their way to try to discredit her work. It was so bad, and so unprecedented, that she actually published a paper about it. You can read more about the bullying here, and she shares her perspective in this interview.

Pre-ordered her book last week and am so excited to dig in! Thank you for your thoughtful questions to Jessica and for giving us a window into this important book.

Thank you for all these resources to learn from and amplifying Jessica's work and book! I'm excited to add it to my list.