How I Became an Antiracist Dietitian

In which a 7-year detour to the Deep South turns into a new path forward

This is the second of two essays laying out the foundation for this newsletter. Last week I talked about why I’m here, and today’s essay is the story of how I got here. Next week we’ll move away from me, and on to more important topics.

I thought I wanted to be a dietitian because I wanted to help people.

I thought I wanted to be a dietitian, but it took almost 10 years to happen, and by the time I got there, after all I had seen, I wondered if dietitians were actually helping people, particularly people of color.

By the time I got there, my definition of "helping" had changed.

I had changed. But how?

I remember the exact moment when I decided I wanted to go back to school to become a dietitian. It was early morning on a weekday. I was eating breakfast and scrolling through Craigslist employment ads looking for some way out of my tolerable but dead-end office job. I was almost 30.

I had recently returned to Los Angeles after a two-year stint teaching English in Central Japan. In Japan, I had discovered a love of food writing, cooking, and food history, but I saw no way to translate that into a sustainable career. I didn't want to work in a restaurant. I had a food blog, but it didn't pay anything.

This Craigslist job though: running the kitchen at a women's homeless shelter and teaching cooking and nutrition classes to the residents. It sounded perfect to me—combining food and education, a job that would make a difference—and one way to be eligible to apply was being a registered dietitian.

This was interesting to me. I thought dietitians just worked in hospitals or school cafeterias. I hadn't realized there was a "community nutrition" career option.

This launched me down a path of part-time community college science classes while continuing to work full-time, then a transition to a full-time dietetic program at a state school nearby. Somewhere in there, I got married, started writing for The Kitchn, was promoted to the editorial team at The Kitchn, and quit my office job to join my friend's personal chef business, cooking for an extremely wealthy family in Malibu a few days a week. I was getting paid to cook and write about food, which a few years before would have been a dream come true—but I thought I could give the world much more as a dietitian, so I kept going.

I timed my pregnancy perfectly to have my son at the start of summer vacation, so that I could finish my last two semesters of school on time. (I know this sounds insane, but it's true. I'm an Enneagram 1, Wing 2, which we can talk about some other time.) Life had other plans, though, and five weeks after our son was born, my husband got the job offer of a lifetime in New Orleans1, and we were off.

Living in New Orleans was an unexpected, confusing, sometimes frustrating, sometimes inspiring and beautiful, seven-year detour that turned into a road toward someplace better for me.

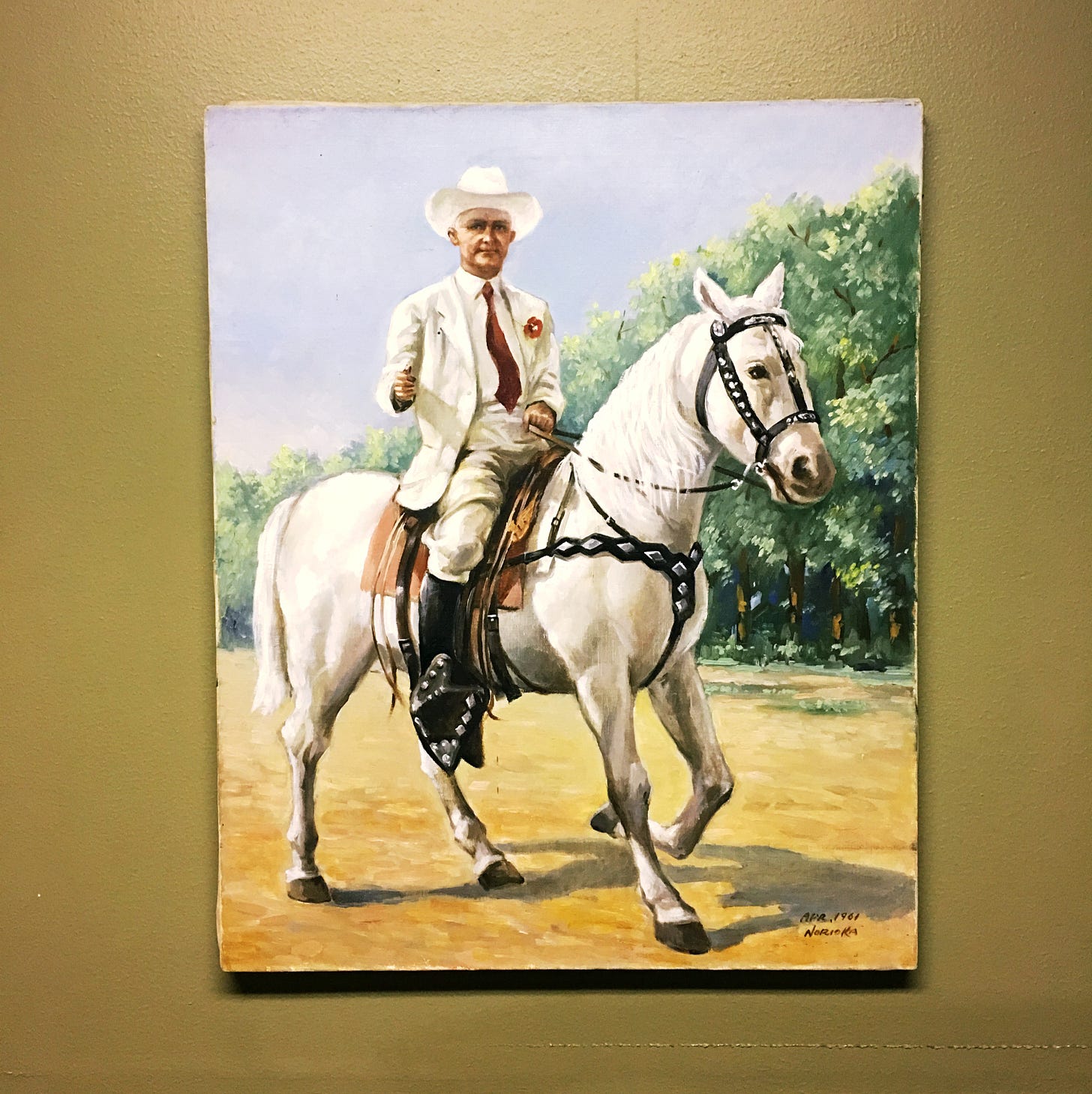

We arrived too late for me to enroll in school the first year, so I spent that time being a reluctant stay-at-home mom and trying to figure out how to spell "Tchoupitoulas." The next year I enrolled in a state school named after a slave-owning former Louisiana governor whose mascot until the early 2000s was a white-haired colonel in a Confederate Army uniform. So that was different!

It was also a radical lesson in cultural humility. I had grown up going to public schools in an incredibly diverse L.A. suburb, where it was normal to speak to your parents in a language other than English, or welcome a new classmate who had just immigrated from another country. But the urban and suburban diversity I had been surrounded with my entire life had actually not prepared me at all for the culturally and geographically distinct world of the Louisiana Cajun bayou.

That first year, I felt like a complete foreigner. I learned to stop making assumptions about anything: pop culture references, eating habits, political views, thoughts on current events, life experiences. But it was good for me to get out of my California bubble, and to see that trying to push my values on people with completely different life experiences than mine was not only pointless, it was deeply patronizing. I thought more before speaking. I listened carefully. I tried not to judge.2

I also applied to start my Master of Public Health program at Tulane concurrently with my second and final year at the state school. Public health was a revelation to me. After years of learning about how to intervene at the individual level, it felt so good to talk about society's responsibility for caring for each other, and all the factors that impact health that are outside of a person's control (otherwise known as the social determinants of health). I remember the first time I heard a professor talk about racism as a public health issue. I was amazed. I took a picture of the slide.

My program wasn't perfect and Tulane's reputation among Black New Orleanians can be problematic to say the least—but being able to talk openly about social justice and fixing systems rather than trying to "fix" individual people restored my passion for food and nutrition. When the school offered a free Undoing Racism training the summer after my first year, I took it. Toward the end of the first day, I looked at a chart the facilitator had drawn, at all the institutions and systems built on white supremacy, and I thought, "The reason I am so over dietetics is that I've never heard anyone admit how racist it is."

I could write a whole other essay about how transformative that workshop was—both as an Asian American who suffers under white supremacy and as a person who has privileges and benefits from white supremacy—but that moment of clarity is the one that transformed my career trajectory. I decided that nothing was more important to me than pursuing racial equity and specifically fighting anti-Blackness, and finding a way to make nutrition and our food system more just and equitable.

The next summer I graduated with my MPH, and prepared for the start of my dietetic internship through Tulane. I had briefly considered not doing the internship (see: being totally over the field of dietetics), but my advisor thought I should just do it. "If there's a job opening and an MPH/RDN is up against someone with just an MPH, the MPH/RDN has an advantage," he told me. Fine.

I didn't know those nine months were going to be some of the hardest, and most illuminating, of my life.

The illuminating thing about my dietetic internship, which involved working at over 25 sites, from food banks to school cafeterias to community gardens to dialysis clinics, was that I got to see an incredibly broad picture of how food, nutrition, and healthcare interact with people's lives. It's like I was making a gigantic diagram of the regional food and nutrition system in my brain.

The hard thing about my dietetic internship was that as this diagram took shape, the inequities in the system were so clear, and the system was so full of them, it was overwhelming. And the people at a disadvantage were always disproportionately Black. For example, the dialysis clinics I worked in were almost entirely attended by Black clients—African Americans are almost four times more likely than white Americans to experience kidney failure, a difference attributed to racial disparities in food, housing, employment, education, and health care—and these undeniable numbers were gutting.

But it wasn't only the patients who were bearing the weight of this unjust system. The kitchens that I worked in and around—in large hospitals, in fancy retirement communities, at schools—were largely staffed with Black employees working at or near the minimum wage, which in Louisiana is the same as the federal minimum wage: $7.25 per hour. SEVEN DOLLARS AND TWENTY FIVE CENTS. (Side note: the state preemption laws that won't allow a city like New Orleans to raise its minimum wage to match local cost of living are also totally racist.) Paid that wage, you would need to work almost three full-time jobs in order to afford a two-bedroom rental in New Orleans. It was and is infuriating.

There was no acknowledgement of these disparities or discussion of their causes in my classes with the other interns, or from the preceptors who supervised me. (Except for one! But more on that later.) I sometimes witnessed racial microaggressions and occasionally straight-up racism from my preceptors. Confronting them in the moment could have led to retaliation, and I had no anonymous way to report these incidents or forum in which to process them with my fellow interns, who I know were having similar experiences.

There was one bright spot: my rotation with Propeller, the nonprofit where I had also done my grad school internship, helping to launch a city-funded program that assisted BIPOC corner store owners with stocking and selling more fresh fruits and vegetables. In my rotation, I was reunited with my supervisor from that program, an incredible dietitian with a deep understanding of the injustices in the food system, especially in and around New Orleans. I was in awe of the work Propeller was doing, supporting entrepreneurs, particularly BIPOC entrepreneurs, who were making a difference in the city, and giving them the tools to operationalize racial equity in their businesses.

As luck would have it, a job opened up during the last month of my dietetic internship, a position running the corner store program that I had worked with in grad school, and assisting with Propeller's business accelerator program. I got the job and stayed for two and a half years, through an unexpected pregnancy and maternity leave, a promotion and a pandemic, and finally a move from New Orleans to Denver.

I loved my co-workers and the work we did together. I loved the entrepreneurs we supported and the partners we collaborated with, and I especially loved that racial equity was at the center of the work we did. It was a safe place to be vulnerable, to learn, to make mistakes, to ask questions, and to be human.

I started my journey wanting to “help” people—but now I am very wary of that word.

I believe communities, especially communities of color, understand better than anyone how to start solving their issues. Often it is money and power that are needed, not “solutions” created by outsiders. How do we empower people? How do we build trusting relationships? How do we make sure we keep showing up, and not disappear the moment the funding or attention or political support are gone? And how do we continue to work through our own internalized racism, and learn and grow from our mistakes? These are the questions I’ve come to ask myself.

…So that was my road from there to here. I am very excited about everything that lays ahead of us.

There is no non-awkward way to drop this into the conversation, so I’ll just say it: my husband is an actor and the job was playing Sebastian Lund on NCIS: New Orleans. Tell your mom; she probably watched the show!

This became really fucking difficult in the fall of 2016.

Thanks so much for starting this newsletter/blog! I need a therapy session with you. Half the time I feel raw, "overwoke" and hopeless about the terrible injustices baked into our culture and our institutions, and the corporate stranglehold on our food supply and the health (sick) care industries. It is inspiring to know, I'm not alone and someone else is working to find some small or large way to address what we can.

I love that you are doing this, Anjali!