Irritable Bowels, Distrustful Doctors & Bloated "Hot Girls"

What IBS diagnosis & treatment can teach us about the sad state of healthcare in the US.

Although I don't have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), I spend a lot of time thinking about it, because Rob, my husband, has it. (Don't worry, he said it was okay that I tell you this.) He suffered with it for most of his adult life, until I was taking a medical nutrition therapy class and saw that his symptoms were an exact match for IBS-D, and gently reminded him that most people don't need to budget time to evacuate themselves before heading out of the house to a location without a public restroom, or worry about having accidents on commuter trains.1 Shortly after that, a particularly over-the-top meal at Willa Jean sent him into a weeklong bout of abdominal pain. After a year of tests, consultations with a dietitian specializing in IBS2, an elimination diet and very slow trial reintroduction of foods, and looking up so many things on the Monash University FODMAP app, he finally figured out that fructans, a type of carbohydrate, were the culprit, and onions in particular were a trigger for his IBS. It is not an exaggeration to say this discovery has changed his life.3

He is an educated, English-speaking white man who had excellent employer-provided health insurance as he went through this process — that is to say, exactly the type of person the US healthcare system is set up to serve. Not everyone with IBS is so lucky. Through the microcosm of racial disparities in IBS we can see the problems in US healthcare as a whole, and we'll end with a look at the weird, mostly-white wellness world of #IBStok.

When There Is No Test

Irritable bowel syndrome is estimated to affect about 9-11% of the population globally, and about 10-15% of the US population. That's a lot of poop problems. IBS is a type of functional gastrointestinal disorder, meaning diagnosis relies on patients reporting their symptoms, rather than testing that confirms presence of a disease. Doctors may run tests or do other procedures to rule out other diseases or conditions which could be causing the symptoms — for example, they might do an endoscopy to check for Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis — but there is no objective test to check for IBS when someone reports their symptoms.

Medical bias frequently shows up in situations like this, where medical professionals have to rely on the subjective observations of their patients. There is well-documented racial bias in how Black patients are assessed and treated for pain, another condition that lacks an objective test and relies on patients assessing and reporting their own symptoms. Research has found that Black patients are less likely than white patients to be given pain medication, and even when they do receive medication, it is in lower quantities.

For example, in a retrospective study, Todd et al. found that black patients were significantly less likely than white patients to receive analgesics for extremity fractures in the emergency room (57% vs. 74%), despite having similar self-reports of pain. This disparity in pain treatment is true even among young children. For instance, a study of nearly one million children diagnosed with appendicitis revealed that, relative to white patients, black patients were less likely to receive any pain medication for moderate pain and were less likely to receive opioids—the appropriate treatment—for severe pain.4

Even more disturbing: researchers examined false beliefs about Black people's biological differences from white people, and found that many white medical students and residents believed incorrect assertions like, Blacks’ skin is thicker than whites’ and Blacks’ nerve endings are less sensitive than whites’. Those who believed in these false statements were more likely to rate the pain of Black patients as lower than white patients, and were less accurate in their treatment recommendations.

First: UGH. What? This was published in 2016, not 1916.

Second: it doesn't come as a surprise, then, that a study looking at racial disparities in healthcare utilization by IBS patients found that Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients were less likely than white patients to be referred to a specialist for care, but more likely to undergo a gastroenterology-related procedure.

Black patients were 3.4 times more likely to undergo either a colonoscopy, EGD [upper endoscopy], sigmoidoscopy, or hydrogen breath test than white patients and Hispanic and Asian patients were 2.6 times and 2.0 times more likely, respectively. While these findings could suggest increased access to care in our minority cohort, we suspect our results instead reflect impaired communication between minority patients and their overwhelmingly white medical providers.5

The authors of the study believe that the "impaired communication" may go both ways. BIPOC patients may distrust the subjective assessment of white medical providers and request a procedure to get a more objective viewpoint. That same distrust may make it difficult for patients to speak openly and comprehensively about their symptoms, so that their healthcare practitioner can make a diagnosis.

And it could be that racial bias makes it more likely doctors do not feel comfortable making a diagnosis based on symptom reports alone, and are more likely to over investigate BIPOC patients by recommending GI procedures. While safe, these procedures are not without risk of complication, and certainly cause more discomfort and even pain than simply reporting symptoms to a provider during an office visit. Were Black IBS patients 3.4 times more likely to endure that discomfort because their provider thought it plausible that their nerve endings were less sensitive, or their skin thicker? Given what we know, it's possible.

Of course, there are other factors that could contribute to these differing treatment recommendations, but many of them also point to the need for racial and ethnic diversity in the medical field. Cultural beliefs about illness and its treatment, cultural stigma around a condition involving the bowels, and stigma around the use of antidepressants to treat IBS can all contribute to a disconnect between patients and providers, if providers are not aware of these differences, or if they approach them with paternalism.

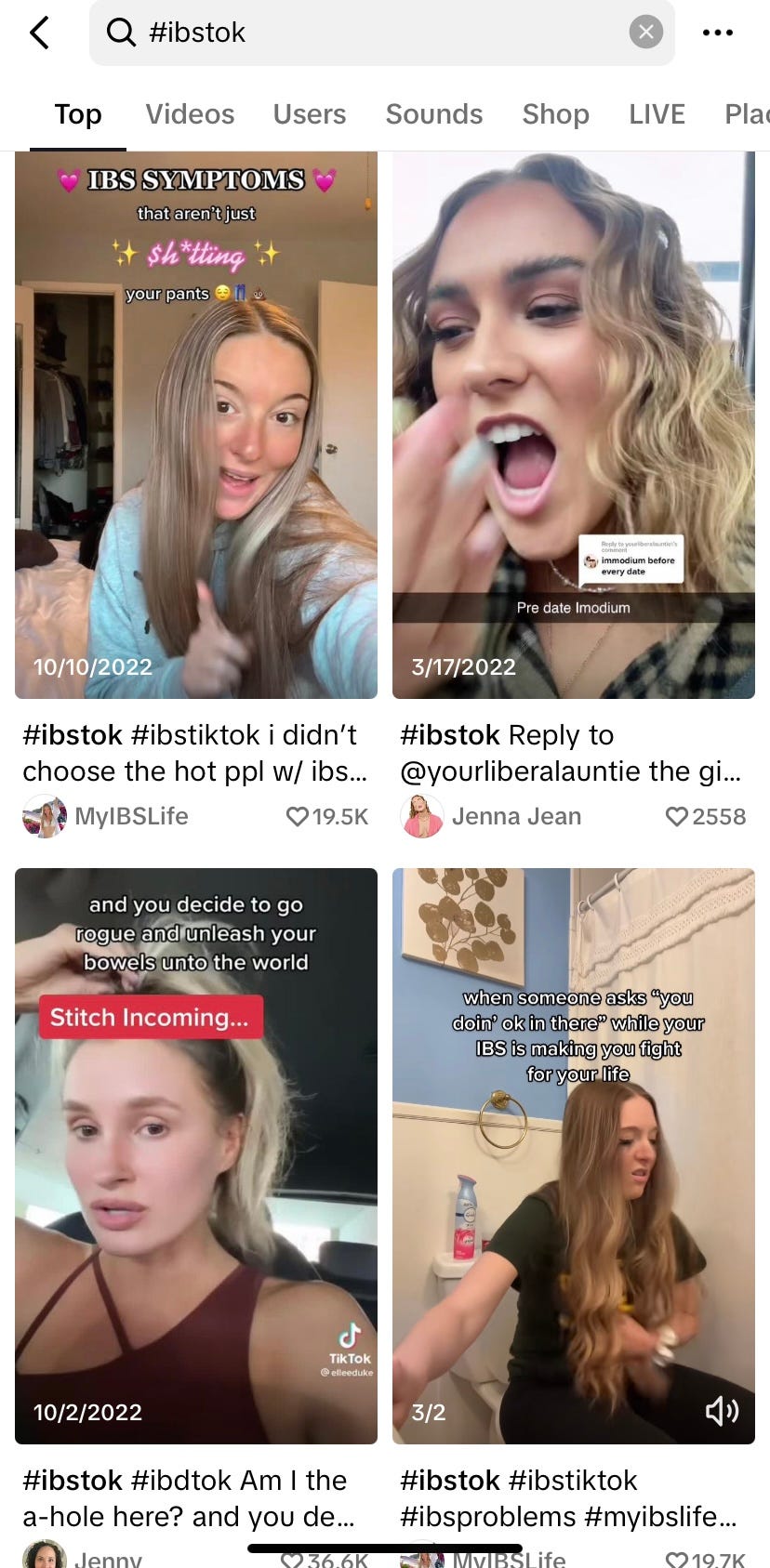

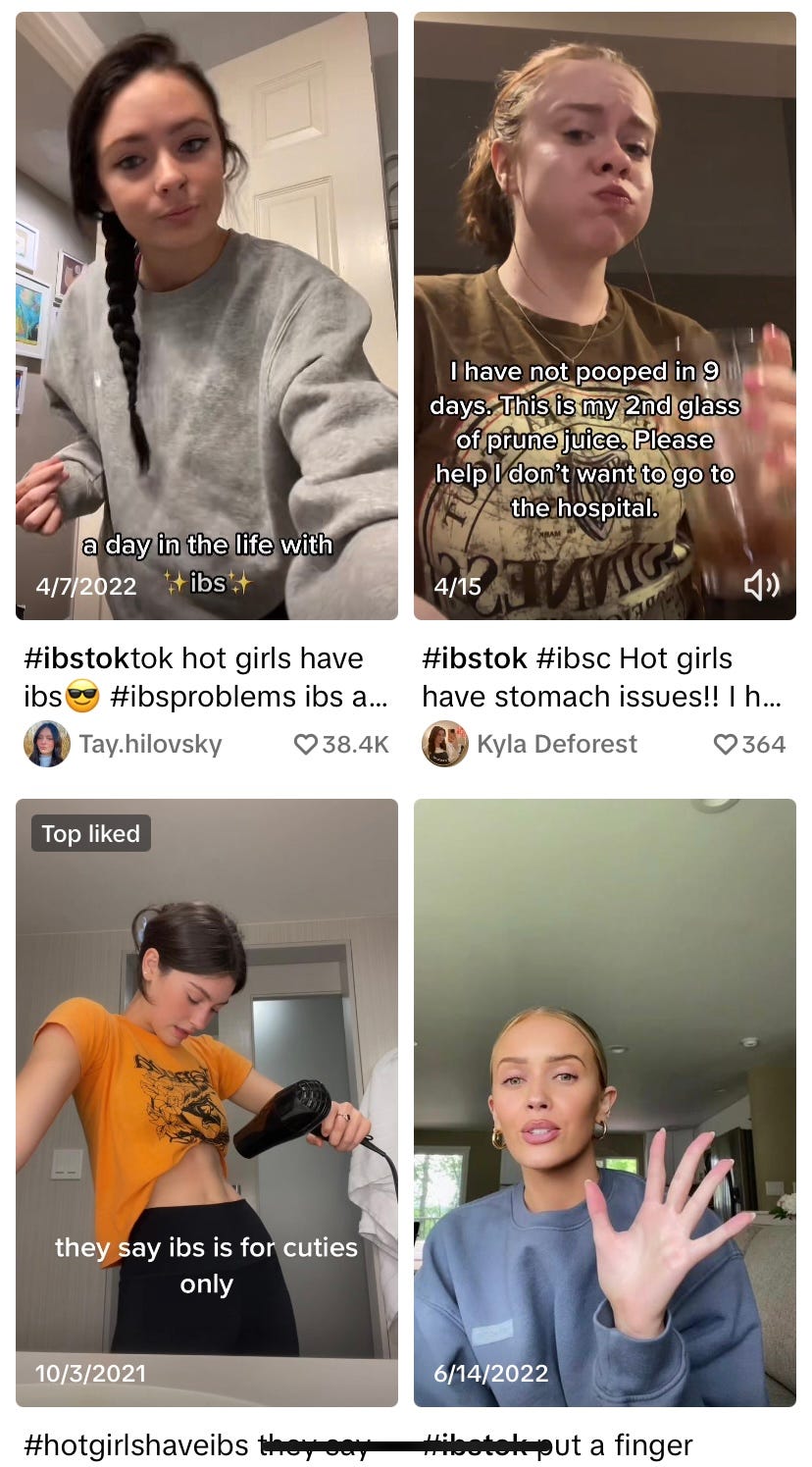

IBS as Social Media Trend

So let's say you are a BIPOC person experiencing IBS symptoms who wants to escape the bias and distrust of the mainstream medical system — where can you turn for help? Perhaps Instagram or TikTok, where IBS talk (or #IBStok) is a somewhat surprising trend? Social media, and the Internet as a whole, is often where marginalized folks look for the help and support they aren't able to find safely or affordably in the traditional medical setting. If you are lucky, you might stumble onto the work of dietitians like Samina Qureshi, who shares culturally- and weight-inclusive advice through her @inclusive.ibs.dietitian accounts. More likely, you'll wade into the swampy mess of pseudoscience, fear-mongering, and diet culture that define so many online spaces dedicated to "wellness."

What you'll also find in these spaces? So many thin white women.

Just so many.

Nutrition-based approaches to relieving IBS symptoms can be incredibly effective (see: my husband and onions), but they do involve following a restrictive elimination diet, followed by an only-slightly-less-restrictive reintroduction diet. It's a long period of carefully measuring your food (two blackberries today, five blackberries tomorrow) and tracking what you eat, ideally with the support of a FODMAP-trained dietitian. This requires careful navigation for those who have past or current issues with disordered eating, and it also requires access to a dietitian, and often the resources to pay out of pocket for their care.

Do you choose the overzealous, mistrustful/mistrusted mainstream medical care that your insurance will cover, or the "hot girls with stomach problems" who are giving you free but questionable advice? It's the worst Choose Your Own Adventure ever.

I have no answers, but I was happy to stumble onto a TikTok from Lauren Bell, giving some science-based information also rooted in her personal experience with IBS. More of this, please.

I know some of you out there work with IBS and other GI disorders — please tell us more about your on the ground experience in the comments! How can we make IBS diagnosis and treatment — and diagnosis and treatment of all diet-related diseases — less biased, more culturally appropriate, and more accessible for all?

Embodying the "you gotta laugh or you'll cry" ethos, he has since repurposed the epic train story into a stand-up comedy routine, which you can listen to below:

My friend and former classmate, Jocelyn Harrison, a Monash University FODMAP trained dietitian. She's wonderful.

And my cooking! AMA about cooking deliciously without onions or garlic.

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), 4296–4301. You can read the whole paper here.

Silvernale, C., Kuo, B., & Staller, K. (2021). Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterology and Motility: The Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society, 33(5), e14039.

Awwwww! Thanks for the shout out! This is such an important topic. In my humble opinion, IBS also speaks volumes about the state of our food supply. There is a reason that IBS is so common and a lot has to do with the easy accessibility of highly adulterated foods. I've also worked with a fair number of patients for whom we've identified dairy as their primary problem. These patients are often BIPOC and much more likely to be lactose intolerant. It doesn't make sense that 3 cups of dairy a day is part of the US Dietary Guidelines when 68% of the world's population has lactose malabsorption.