The Mediterranean Diet Is a Whitewashed Fantasy

And why are we even talking about a "gold standard diet" anyway?

It's a new year, and time for the annual pushing of the Mediterranean Diet. "The Mediterranean Diet Really Is That Good for You. Here’s Why," proclaimed the New York Times a couple weeks ago.

“It’s one of a small number of diets that has research to back it up,” said Dr. Sean Heffron, a preventive cardiologist at NYU Langone Health. “It isn’t a diet that was cooked up in the mind of some person to generate money. It’s something that was developed over time, by millions of people, because it actually tastes good. And it just happens to be healthy.”

He then adds everyone's favorite non-inclusive dietary advice:

People who follow the Mediterranean diet tend to “eat foods their grandparents would recognize,” Dr. Heffron added: whole, unprocessed foods with few or no additives.1

(Pretty sure my late Thai grandparents wouldn't recognize smashed avocado toast or low-fat Greek yogurt, two snacks the article suggests. But I digress.)

But about that first quote—I have some questions about that, because I've read Kate Gardner Burt's 2021 paper in the Journal of Critical Dietetics: "The whiteness of the Mediterranean Diet: A historical, sociopolitical, and dietary analysis using Critical Race Theory." Her thorough and thought-provoking history and context for the creation of the Mediterranean Diet, and critique of the scientific methodology behind the diet's purported success had me nodding along and aggressively highlighting my PDF. I reached out to her for some thoughts on this paper, and her work in general.

Dr. Burt is an assistant professor and undergraduate program director in the dietetics, food, and nutrition program at Lehman College, CUNY in the Bronx. She is also one of the few registered dietitians whose research centers issues of diversity and inclusion in the field, and she established the #InclusiveDietetics Facebook group with fellow registered dietitian, Shelly DeBiasse. Her students are much more diverse than the usual class of nutrition students, as you would expect from a college in the Bronx, with students of all ages, from all over the world. Conversations with her students—hearing their feedback and occasional pushback on white-centered nutrition curriculum—often drives her to look more deeply into issues, and sometimes leads to published research like this. "I couldn't do this work without the students and the conversations that we have in the classroom," she told me.2

You can and should read the full paper in the open-access link above, but in the meantime here are some of the key whitewashed fantasies about the Mediterranean Diet that it uncovered for me.

Fantasy #1: The Mediterranean Diet reflects the diversity of foods eaten in the Mediterranean region

There are 21 countries that border the Mediterranean Sea, including countries in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East: Albania, Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, Slovenia, Spain, Syria, Tunisia, and Turkey.

You can see the region encompasses a huge diversity of food and cultures. But the Mediterranean Diet is most commonly associated with Italy and Greece, two countries in the famous Seven Countries Study whose foodways were found to have lower amounts of saturated fat and whose study participants had lower rates of cardiovascular disease and related deaths, when researchers were conducting the study beginning in the 1950s. (The countries in the study were mostly populated by white people, and the participants were all men.)

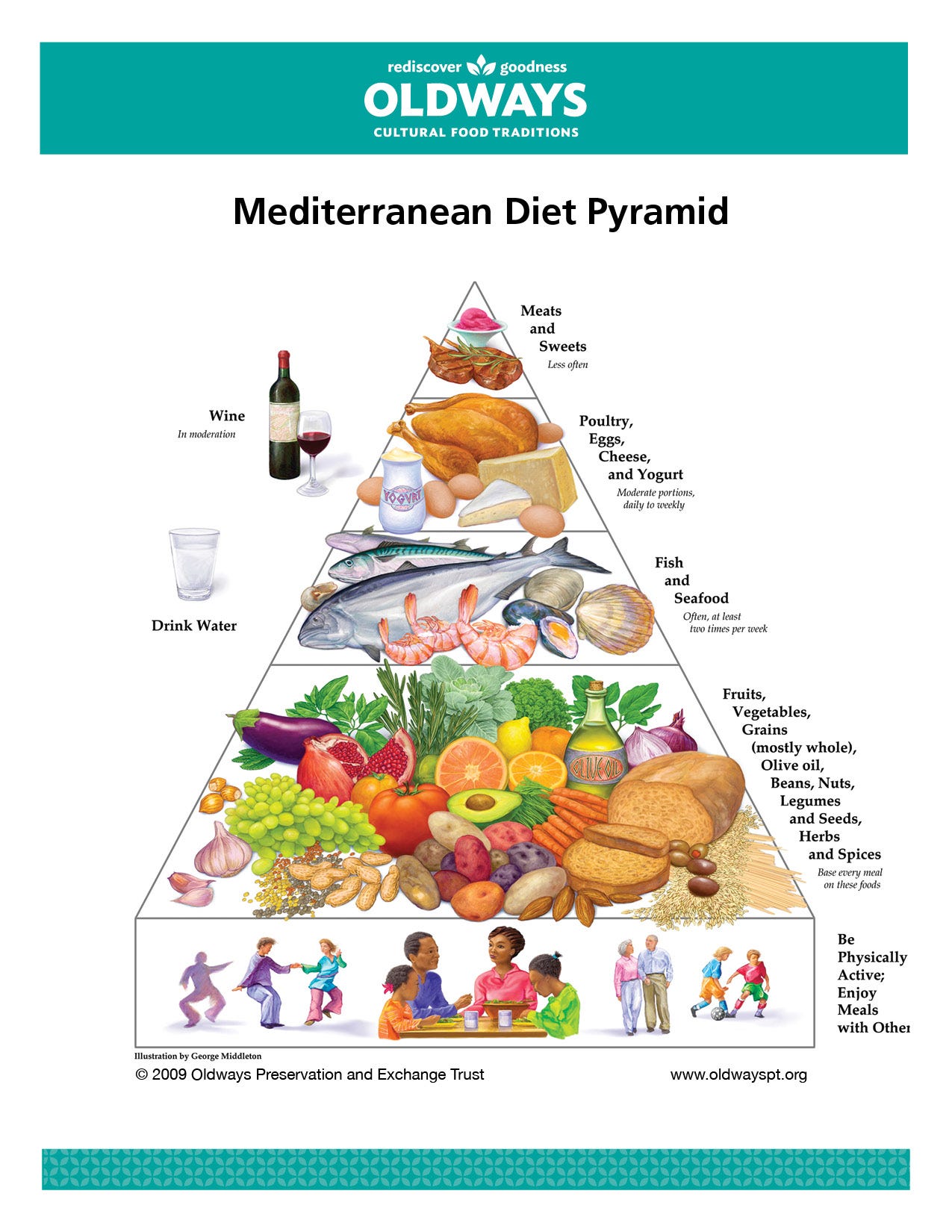

In 1993, the Mediterranean Diet was used to create the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid (MDP). Burt points out:

The authors of the MDP, mostly white men affiliated with Harvard University (and in partnership with the non-profit organization Oldways), stated that the MDP was based solely on Italy and Greece and that it “describes a dietary pattern that is attractive for its famous palatability," begging the question: famous among whom? It was famous among white Americans, who romanticize and exoticize the Mediterranean region.

White Americans' romantic visions of the Mediterranean region do include Italy, Spain, and Greece, but are unlikely to include places like Syria, Lebanon, or Tunisia, places that typically appear in Western news with headlines of war, turmoil, and protests, not travel and food.

The International Foundation of Mediterranean Diet's (IFMeD) is "a pole of MULTI-DISCIPLINARY KNOWLEDGE and EXPERTISE internationally recognized for the RE-VALORIZATION of the Mediterranean Diet." (Yelling words theirs.) Burt calls attention to the fact that its International Scientific Committee, which analyzes and translates scientific information about the diet, is composed of members who are mainly from Italy and Spain, with no representation from the Middle East, and just one member from an African country (Morocco).

It's no surprise that, then, that:

The foods recommended by the MedDiet are a subset of foods acceptable by white European/Americans, rather than foods of the region it purports to represent, perpetuating white normativity under the guise of inclusion….[W]hile vegetables and cereals are a base of many Mediterranean cultures’ cuisines, the MDP does not depict cassava/yuca, teff, or many other foods that fit the MedDiet nutrient profile and are indigenous to the Mediterranean region, but are uncommon in a white diet.

When IFMeD's International Scientific Committee revised the MDP, they created a "simplified mainframe" that grouped Mediterranean cultures as follows: Spanish, Greek, Italian, Moroccan, Middle East, French, and Others.

Huh. That's simplified, alright!

Fantasy #2: The Mediterranean Diet is based on a real diet, traditionally eaten in a real place

Let's talk about the idea that the Mediterranean Diet is "something that was developed over time, by millions of people, because it actually tastes good," as stated by the cardiologist in the New York Times. The diet is presented as if it is a blueprint for how people actually eat in a place like Italy, and that people in this imagined place have been eating that way for years. (At least long enough for their grandmothers to recognize the food, you'll recall.)

Where is this land where grandmothers have been eating smashed avocado toast on whole-grain bread and low-fat Greek yogurt topped with fresh fruit since they were young? (The only places I can think of are maybe Malibu or Berkeley, CA.)

Even the NYT commenters are unwilling to prop up this fantasy. Says one reader in Italy:

Trust me, my grandparents, all four of them Italian, never ate avocados, let alone smashed them on toast for breakfast. You guys are falling into the romantic Italy trap—breakfast here typically consists of a few cookies dipped in caffè latte, or a brioche or cornetto at the local bar on the way to work. Here in Central Italy, people are seriously into pork and pork products. And no self-respecting Greek would eat low-fat yogurt.

A reader in Spain:

I have lived in different parts of the Mediterranean for 40 years and the description of the "Mediterranean diet" mentioned in this article bears little resemblance to what people here actually eat. First of all, no one but health fanatics eats "whole grains." It's white bread, white pasta, white rice, couscous, pizza etc. Most people rarely eat avocadoes and never for breakfast, have meat at least once a day, partake liberally of all sorts of preserved meats, cheese and full fat yoghurt and have a lot of milk in their coffee. It is common to have a three course meal in a restaurant that contains no vegetables (e.g., spaghetti with clams, veal saltimbocca, tiramisu), and most people who have wine with meals drink more than a glass (a quarter litre is typical).

So if the Mediterranean Diet is not an accurate reflection of the specific diet in any particular place, what does it reflect? Politics and nutritionism, argues Burt.

She points out that Oldways—the non-profit that partnered with the Harvard School of Public Health and the WHO to develop the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid—"is partially funded by the Whole Grains Council, which receives funding from Barilla, Subway, Kellogg’s, USA Rice Federation, Canada Bread, Tyson foods, and Quaker Oats, among others." Grains, naturally, fill the largest portion of the MDP, though the Seven Countries Study found that some cultures in the Mediterranean region obtained just 36% of total calories from grain-based foods.

The recommendations for how often to eat animal products (poultry, fish, eggs, and red meat) also differ from the evidence; for example, it is recommended that red meat be consumed about once a month, but Italians in the 1960s ate about 5 ½ ounces of red meat daily. Because US eaters consumed even more than that, and saturated fat was blamed for higher rates of heart disease, the Mediterranean Diet recommended levels of red meat consumption based on assumed health benefits rather than the actual diet patterns of people in Italy or Greece.

Burt sums it up:

In this way, the MedDiet is not an actual way of eating for any Mediterranean culture(s); it is an idealized eating pattern created using foods that seem to have desirable nutrient profiles. The MedDiet doesn’t exist outside of its construction in scientific literature.

Fantasy #3: The Mediterranean Diet is the gold standard among all cultural diets

It is no secret that there are real issues with health science that draws its conclusions from evidence almost entirely gathered from white men. The Mediterranean Diet is yet another example of the assumption that what works for white men (and sometimes white women) will naturally work for everyone.

MyPlate is another prominent example of this assumption, and Burt has a paper in review right now that involved street intercept interviews in New York, asking about 3,000 people about MyPlate. "It turned out that white Europeans felt like MyPlate represented them better than the average American, [better than] the non-white Americans," she told me. "So in that difference we can see who these standards are catering to."

After the Seven Countries Study revealed a correlation between saturated fat and heart disease, and the potential role of the so-called Mediterranean Diet, it was followed by a large number of correlational studies looking at health outcomes related to the diet. But, writes Burt:

This research trajectory begs the question: have researchers objectively established that the MedDiet is a dietary pattern that prevents disease or is nutrition science suffering from decades upon decades of confirmation bias?

If you simply keep studying one diet over and over again, how does that prove it is the "gold standard," when the health of populations eating different cultural diets are rarely, if ever, examined at all? It's like a race with only one participant. And isn't the idea of one diet "winning" over every other diet in the world itself an expression of the white normative culture the Mediterranean Diet embodies?

Burt agrees. "This is truly a white normative value—that something has to be the best, and we have to aspire to that." She sees it in the search for hierarchical structure and a specific endpoint in our diets, rather than valuing communal, regenerative qualities like community, support, and growth. "To create this end point that we're supposedly trying to get to feels not only scientifically misleading—because we have no idea what any kind of dietary endpoint would be—but it doesn't actually help anybody."

If you are looking for guidance on a dietary endpoint, look no further than the New York Times article. "How long do you need to follow the Mediterranean diet to gain benefits?" says one sub-heading. The answer: "ideally for [your] whole lives." No pressure!!!

Fantasy #4: Anyone can critique the Mediterranean diet

(This is a fantasy that emerged as I was working on this essay. It wasn't created by researchers in the '50s; it existed in my own head, created by privilege.)

Kate Burt is a white woman, and the reaction to her paper has been both positive and negative. There has been a lot of interest in the dietetics community, and she has been invited to speak to state dietetic organizations, and to organizations that employ dietitians. At the same time, she has seen chatter about her work on sites like Reddit, and it is what you'd expect. "There have also been people who have questioned a lot of the methods, and a lot of my findings—who just chalk me up to being some extreme leftist liberal snowflake."

This reaction, and likely the reaction I will receive for writing this essay, are nothing like the vitriol Lauren Bell (@nutritionlo) faced, after posting on TikTok about the Mediterranean Diet. Bell—a Tulane University professor with a master of public health—is a Black woman, and European TikTokers did not appreciate her take, though it was essentially the same as Burt's and mine. She pointed out the valorization of countries like Italy and Greece, when the building blocks of their diets are very similar to other cultural diets around the world.

"I was thinking a lot about it, and I was like, This is ridiculous, because the Mediterranean Diet, at the root, is all about having fresh fruits and vegetables, having healthy fats, and seafood- and poultry-based dishes, and the majority of the world eats like that," she told me. "And I made a video on TikTok to talk about its relation to public health, and how doctors often push that diet on people without talking about cultural nuance."

The initial reactions were positive, but sometime after she went to bed, TikTokers in Italy and Greece found the post, and unleashed in the comments. She woke up to hundreds of comments talking about "Mediterranean supremacy" and other blatantly racist statements. "I got some comments about how I would only be satisfied if it was Nigerian food on the list," she said. "I'm not Nigerian, so…what are you talking about?"

Her reaction was not to turn away from the hate, but to highlight it in subsequent TikToks, and on Instagram. "There is a lot of rhetoric and discourse around people being overly sensitive, especially Black women, and that's been going on for forever. You know, we're overly dramatic and overly sensitive when we talk about this stuff, and that's not true," she told me. "We get a lot of hate all the time simply for existing."

So who gets to criticize the Mediterranean Diet? As with all things food-related, it depends on your proximity to whiteness.

To support Kate Burt's work, join the #InclusiveDietetics Facebook group. (I'm in it too!) To support Lauren Bell's work, follow her on TikTok and Instagram.

"Don't eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn't recognize as food" is the Michael Pollan quote that launched a thousand food-shaming comments on the Internet.

has a great essay on why that advice is problematic.One way Dr. Burt leverages her privilege is by regularly bringing on students as co-authors on her work.

"No self-respecting Greek would eat low-fat yogurt" I will forever think of this when people bring up the MedDiet

So appreciate your breakdown and the additional resources you shared! It has been so frustrating being in work settings with other nutrition professionals who do hold the Mediterranean diet to a gold standard, without nuance, and can't see how myopic it is.